Fire Power: 12 Versus 20

This time of year, the waterfowl hunting that remains is moving steadily south, down the flyways to the deltas and gulfs. It’s also when hunting in flooded timber comes into its own and decoys move from essential to mandatory. Shooting at its best will be over the dekes, and at treetop height, whether in the trees or in open ponds or flooded fields. So, is there a case to be made for the 20 gauge versus–or if not versus, then being equal to–the 12 gauge this time of the season?

First, let’s get over the idea that the 20 is a “small” gauge, implying that its recoil, and its hitting power are negligible. In the first place, the guns are lighter, meaning that felt recoil, especially with 3-inch loads, can be something more than noticeable, but more than tolerable. Lighter makes them easier to carry, though, especially across a muddy field or wading a distance into flooded timber. Being lighter, they may also swing faster, which in some hunter’s hands can mean they may be too quick to acquire a target, leading a hunter to get too far ahead, or to try to slow down too abruptly. Many hunters have, with 20s and 12s, learned that they may not shoot their best, even on upland birds, with fast, short-barreled guns, and have replaced stubby 24-inch ones with 28s, leading to slower but smoother, more controlled swings. Proving that, at least in this case, more, rather than less, is more.

As far as hitting power, an ounce of No. 2 shot is going to put a more than adequate pattern on a decoying duck. At closer ranges in timber and from a blind, with the proper match of shotgun and shell, and hunter, misses would have to be classified as pilot error, not any inherent deficiency in the gauge.

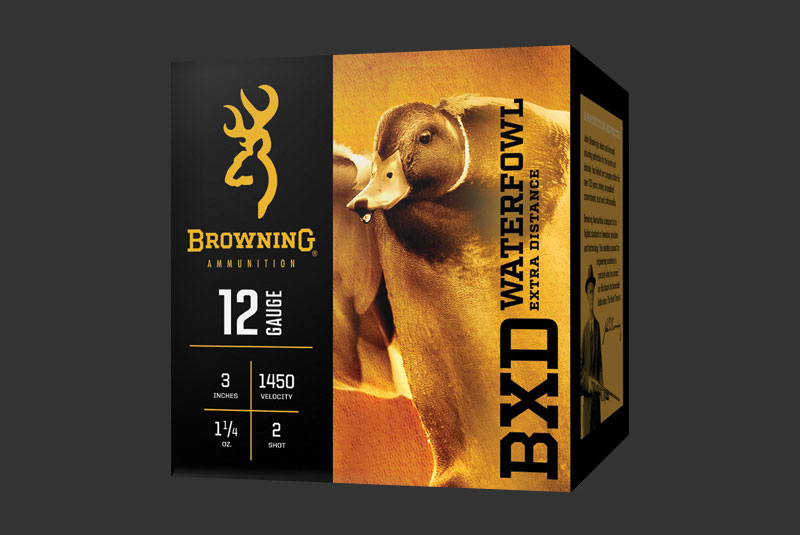

Browning’s BXD Waterfowl Extra Distance loads in both 20s and 12s have advanced wad technology to deliver denser patterns of round, plated-steel shot on a duck. The best shell is one piece of the mosaic. Late season can be more challenging than early for obvious reasons. Those bright-orange-footed mallard drakes are not the drab, callow lads you may have slain in the early fall up in Alberta or Saskatchewan. These birds have been getting shot at for about 2,500 miles for months. The ones that make it are waterfowl Einsteins. (Of course, they have also been feeding in harvested corn fields on the way down, instead of assorted grasses, bugs, and crustaceans; so there is that to be said for why fat ducks this time of year are worth the candle, as they have it.)

Four things, at a minimum for ducks this time of year: scouting, hiding, patterning, and practicing, not necessarily in that order, before you start fretting over gauges. That great old gentlemen of shotgunning, Bob Brister, said, in spirit anyway, because he was talking about something more specific, but the sentiment holds, “I can feel only slightly sorry for a man who has never patterned his gun…I can feel extremely sorry for the ducks that man shoots at beyond the clean-killing range of his particular gun and load.” Spend the money to practice with your duck-hunting loads, if you can find a range where waterfowl shot is permitted: Even a box of shooting helps. Scout where the ducks are “pitching” into, and use that to decide the size of your spreads: Five or six ducks at a time, maple-leafing through the trees, can be drawn in with a smaller set than large flocks over big water, especially where there is little competition from other shooters. Remember, these are wised-up ducks: Hiding is critical, unless you enjoy the artful display of ducks flaring off in sweeping aerial maneuvers.

Two last thoughts: Know your range; look for those gaudy feet and even those bright eyes, before touching off your shot. Use a good dog: The waterfowl you conserve not only may be your own, they’re everybody’s.

Follow Browning Ammunition’s social media channels for more hunting and shooting tips and updates on Browning Ammunition supported events and promotions on Facebook, You Tube, Instagram and Twitter.