How Lifelike Animal Targets Help Improve Shooter Accuracy

Back when my grown son was in grammar school he committed to memory every “The Far Side” cartoon by the genius Gary Larson. Because of that, there was seemingly no situation in which he could not interject, “That reminds me of a Gary Larson cartoon…,” followed by his description of the panel and the caption. Somehow, we all survived as a family. So I am reminded of a “Far Side” cartoon of two buck deer in conversation in the woods, one with a distinct bullseye on his chest.

Luckily for deer, and not so luckily for us, deer–or any other game, for that matter–do not come with preprinted targets on their hides. Yet many of us limit our shooting practice solely to 10-rings or even cardboard boxes; lined pages smirched with Magic Marker® crosses, torn from spiral notebooks and tacked to fence posts; the labels on empty three-pound coffee cans; or the blaze on a dead tree. It’s like learning surgery based on stick-figure anatomy charts.

The anatomy of big-game animals is vital knowledge all hunters should possess. A fortunate hunter I once spoke with, who had drawn a coveted Wyoming bison tag, was asking me about where to shoot to bring down one of the enormous shaggy beasts. The bison heart lies very low in the chest, behind the elbow of the foreleg, and is exposed when a bison steps forward with the leg. Shot there, a bison will bleed out, rapidly though not always instantly. A much larger target is the huge lungs above the heart; and a shot there is fatal, as well. The shoulder is not a good choice because it may only hobble a 2,000-pound animal, giving it a chance to get away, and the bullet can destroy edible meat; and the shoulder hump is all spinous process and choice cuts, making that another inadvisable target.

Whatever animal a hunter goes after, that hunter is obliged to familiarize himself, or herself, with that animal’s anatomy. And with the internet there is a shot-placement illustration for almost anything we might want to give chase to. There are also useful books available on perfect shot placement for both North American and African game by Craig Boddington and Kevin Robertson, respectively, among others.

The online writer Chuck Hawks offers the following useful chart on the size of the vital-organ areas on North American big-game:

- Pronghorn antelope = 8.5”-9”

- Small deer = 8.5”-9”

- Medium size deer = 10”-11”

- Large deer = 11”-12”

- North American wild sheep = 12”-13”

- Mountain goat = 13”-14.5”

- Caribou = 14.5”-15.5”

- Elk = 14.5”-15.5”

- Moose = 18”-21.5”

Hawks suggests that that makes a 9” paper plate a good economical target for judging how far you can hit the vitals on any big-game animal–the maximum ranges at which you can keep all your shots in the plate from any field position is as far as you want to shoot, whether standing, kneeling, sitting, or prone.

The best practice would be on life-sized paper targets, especially ones that display the vital areas. Turkey targets, such as those you can either download online or get from a local gun shop often have the anatomy printed on the target, so you can see where your loads will hit on the bird, not simply on paper. Others for big game, may have bullseyes superimposed over the heart and lungs. The better choice is the ones that either outline the lethal areas lightly, or use a faint x-ray of the skeleton and organs, or best of all, have the vitals printed on the back side, meaning all you have to aim at is the animal’s body, the way it would be on a hunt.

In South Africa some years ago, hunting with an outfitter in the painfully beautiful Waterbergs, I was shooting a borrowed 308, one of the undoubtedly most accurate deer

cartridges extant and ideal for the impala, blesbok, and even warthog I hoped to take. The outfitter, Ant Baber, took me out to his shooting range to sight in “off the sticks,” and sitting and kneeling. Instead of standard bullseye targets, though, he had rather finely hand-painted animals, with the organs on the reverse in the proper location to conform to the front of the animal.

As I shot, troubling echoes of the advice of the late artist Bob Ross sounded in my head, sayings such as, “Just go out and talk to a warthog–make friends with it,” or something to that effect. I didn’t seem to be doing very much in the way of art appreciation; but after a round of shots, I unloaded the rifle and Ant and I walked downrange to look at the target. “Disappointing” would have been a mild characterization, with holes everywhere through the back but where they ought to have been.

We walked back, and this time I bore down, recognizing that I would not be shooting for a bull’s eye, but a living animal’s heart.

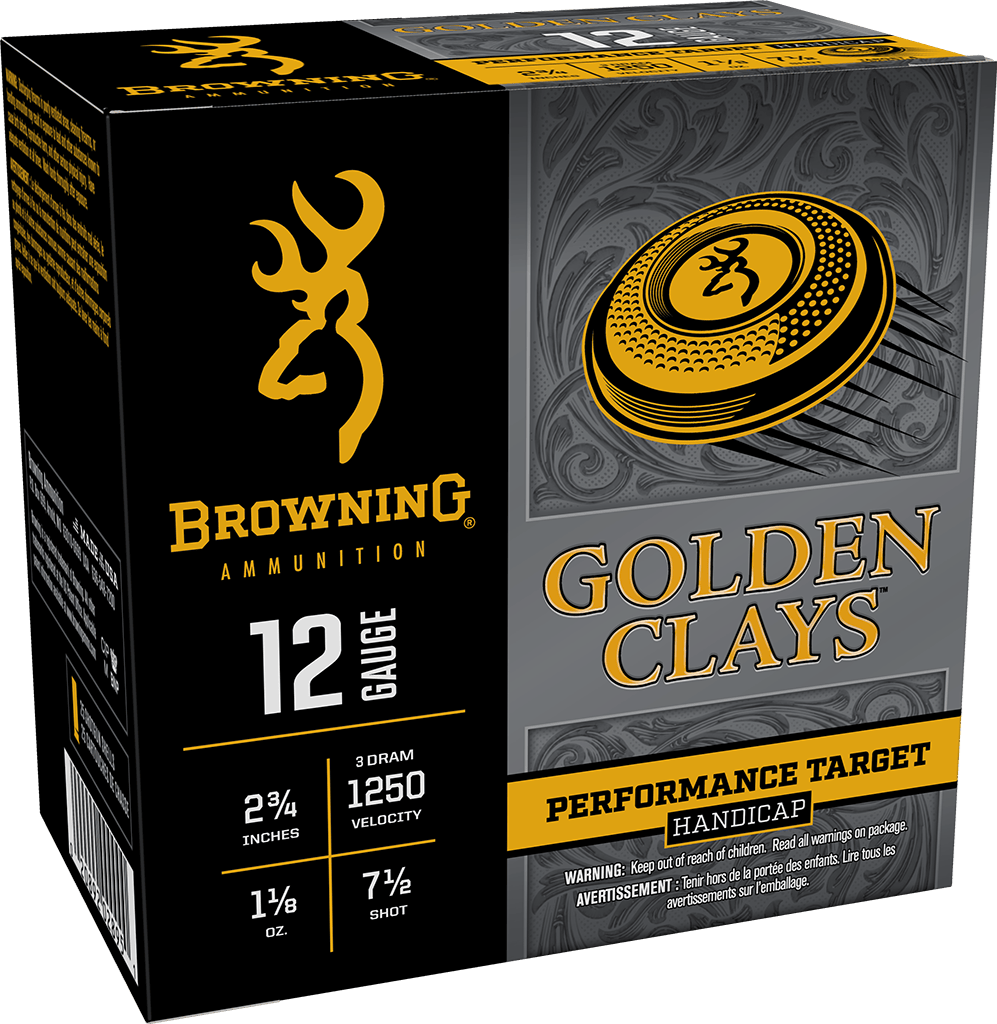

Follow Browning Ammunition’s social media channels for more hunting and shooting tips and updates on Browning Ammunition supported events and promotions on Facebook, You Tube, Instagram and Twitter.