Up We Go – High-Flying Pheasants

“High birds” seem an English obsession. But that may be due to the high cost of pheasants.

In England, pheasants are almost exclusively bred on shooting estates to provide sport for the owners and their guests, paying or otherwise. And “shoot” is the operative word. (“Hunting” in Britain refers to riding on horseback, following the hounds that are chasing the foxes–or used to be; chasing real foxes is now disallowed, and “hunts” take place along dragged scent trails. Of course it may also refer to something called “hunting the clean boot,” in which bloodhounds follow a human trail. What we know as deer hunting, the English know as “stalking”; and shooting is exclusively reserved for bird hunting, though it might also be called “wildfowling” when it’s for ducks and geese, or “falconry” or “hawking” when done with raptors. Got that?) If a shoot is a “driven” one, rather than a “rough” shoot, the price in England can be astronomical.

Back in the era of the Victorian and Edwardian shoots, when you might be entertaining the Prince of Wales as one of your invited guests, there was the raising of the birds, the upkeep of the estate, the employment of a first-rate gamekeeper, a corps of beaters who had to be hired for the weekend, the multi-course dinners, and the just plain extravagance to be taken into consideration. None of it could have been possible in an age that was not one of conspicuous consumption, even with the amount the dead pheasants might bring when taken to market.

Which is why the saying was, “Up flies a guinea, bang goes sixpence, and down comes half-a-crown.” If you’re not up on the value of your old English money, just realize that it means that the cost of raising and shooting a pheasant was almost nine times the cost of what you could sell it for, according to the axiom. Today, landowners lease out their shooting at anywhere up to $3,500 per gun per day. And shooters will pay that in no small measure for the chance of taking high birds, birds flying as much as 50 yards up.

We Americans don’t get the amount of high-bird shooting the English do on their driven shoots. A flushed pheasant may come over our heads, but more likely will be rising to about 45-degrees above us, and not screaming at 90-degrees straight up, the way a bird in the UK, driven off a bluff, might. We do get passing ducks speeding above us, and the most common high bird we are likely to see in this country is the dove, white-wing or mourning. Practicing for high birds is very much worthwhile, though, because it does reinforce the fundamentals of wing-shooting applicable to almost any bird we might see above us.

For practice, you really need to locate a range with a tower for launching targets from, for realistic shooting. One thing to remember is that a clay target is losing velocity as it travels away from a tower, while a wild bird in flight above us will be picking up speed as it senses the danger increasing.

If there is a single lesson that practicing for high birds applies to every variety of wing-shooting, it is: Keep your head on the stock! The only rear sight attached to a shotgun is the shooter’s eye, and whenever you lift your head off the gun to see where a bird is flying, you break your sight’s connection to it; and unless your cheek is welded to the comb when you shoot, other considerations, such as length of pull, comb height, cast, choke, and the rest, will be next to useless.

With the gun at the ready, pick up the line of the bird’s flight with the muzzle or muzzles and then raise the barrel(s) staying parallel to the original line as you mount the gun. Don’t let the muzzle wave around like a conductors baton. For high birds, don’t let your hand be too far out on the fore-end. You see trap shooters with their hands pushed all the way forward, even resting the far part of the fore-end in the V of their index and middle fingers; but that may not give a shooter enough range of movement when trying for high birds.

Other homework with an unloaded gun would be practicing shifting the weight from your front leg to your rear one as you recreate your overhead swing. You never want to feel like you are losing your balance or tangling up your feet, and working on that in the privacy of your own home could be less embarrassing than out on the range, in public.

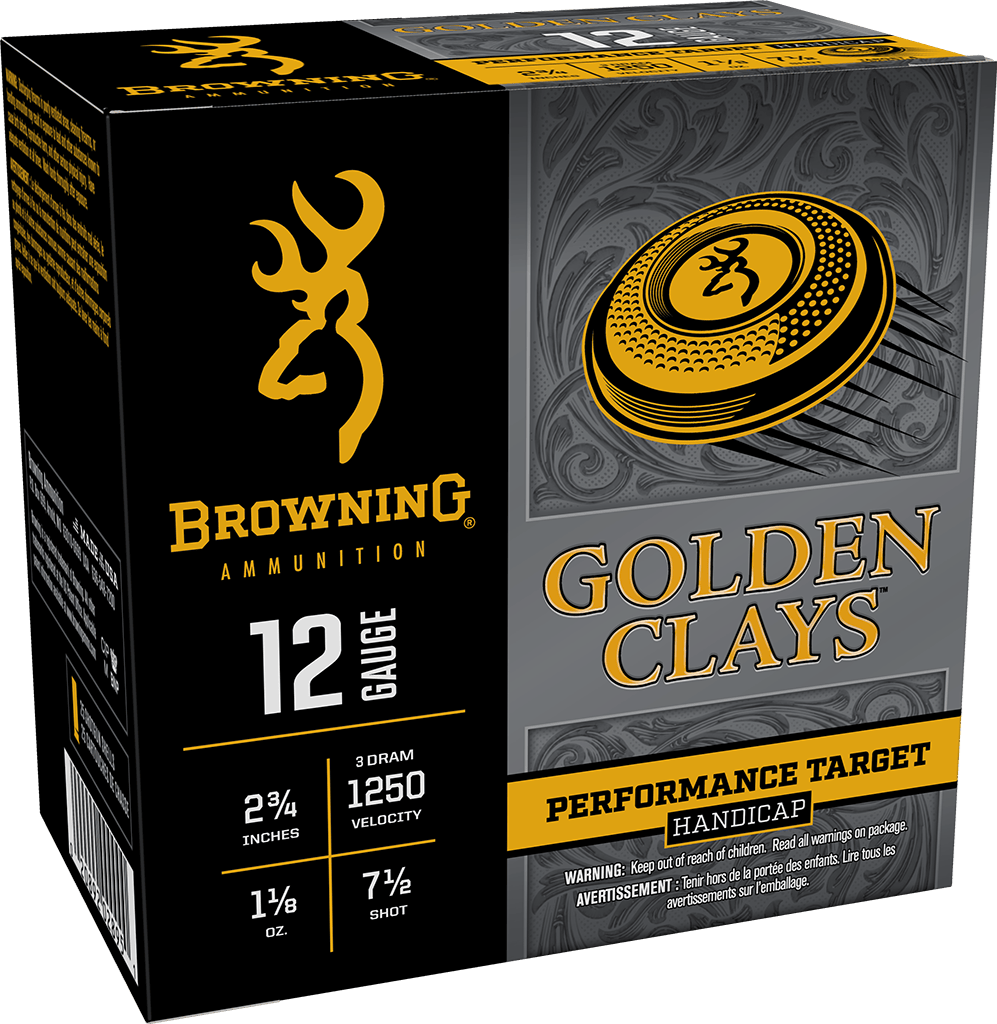

If you think you might be running across some high birds on a pheasant hunt, have some No. 5s to go along with your 6s. And make sure you have a stout enough load, such as Browning BXD Upland Extra Distance 12 gauge with 1⅜ ounces of nickel-plated shot. If you wanted to cover the bases, you could load your 28-inch Browning Citori CXS with No. 6s in the bottom barrel, choked Improved Cylinder, then with No. 5s in the top, choked Modified. Select for the lower barrel first, to reduce muzzle rise before a second shot, and you have a generous pattern for an incoming bird; and if you miss with that one, you have the over barrel if it starts to soar.

Twenty-eight inch? The extra length will slow and smooth your swing, and you want slow and smooth for high birds, above all. Another tip, in keeping with the Anglophile theme, don’t rush your gun mount. English shooters on the range will start with the butt of their gun at the crook of their arm. Calling pull, they won’t rush to bring up the gun when the bird comes into sight, but will recite in their heads, “God save the Queen,” as they mount to shoot. At that point, there’s little that can save a clay target.

Follow Browning Ammunition’s social media channels for more hunting and shooting tips and updates on Browning Ammunition supported events and promotions on Facebook, You Tube, Instagram and Twitter.