Rome Alone for Upland Birds

Henry David Thoreau wrote that the person“who goes alone can start today,” and the same may be said of the hunter: If you have to wait on your friends before heading into the pheasant field, you may be waiting a long time. When we are after deer or turkey and other game, we are used to being in the woods by ourselves, even if we are sharing a camp with friends. Pheasant hunting, though, seems to some to call for a platoon to drive the cornfields, too often taking on the aspect of a thin-orange-line version of those Highlanders at Balaklava. Despite that, there are times when it doesn’t take a village to raise a rooster.

With or without a dog–and let me interrupt here to note that some hunters are self-conscious about working with a rough-hewn dog, even by themselves; frankly, there is nothing better than being with an eager dog with natural bird sense, even if you have, so far, only reliably trained it to do nothing more than sit, stay, and come, particularly if it starts to range. If you can begin from there, you will be farther than halfway to a polished hunting partner. Besides, what better time to bring a dog on a hunt than when nobody’s looking? Once again, with or without a dog, there are ways for a single shooter to put birds in a hunting vest.

Those narrow strips of cover along fence lines that can look inviting to the hunter alone may mean having to push the birds hard enough to get to the end before they take straight off out of range. Some hunters seriously advocate the loner’s, especially sans man’s best friend, pushing a small strip of cover by, if not quite running, then at least jogging through it, observing as many safety precautions as possible. However, the only thing more foolish than running with scissors may be running with shotguns. To be truly safe, a hunter should carry an unloaded gun. Even then there is the risk of a sudden trip and fall, with merely landing on the steel barrels and action of a gun causing injury. Or worse for some, damaging a fine firearm (and remember that if you are alone, even with your dog, your dog can’t drive you to the ER or dial 911)–which makes catching a wild flushing bird rather problematic. Consider as well that the average walking speed of a human is just over 3 miles per hour. A healthy jog would be about double that. A rooster pheasant covers ground at up to 10 miles per hour. You do the math. So, take an opposite tack: cunning and stealth versus vigor and speed.

It starts with climbing out of the pickup or car. Do not slam the door! Close it quietly. Better yet, park some distance away from where you plan to start hunting and walk in, softly. Move quietly at a brisk, safe pace, without crashing around. If you do have a dog, keep it close. Small clumps of cover, the size you can shoot across, are good places to approach silently; but don’t be daunted by large patches. For one thing, there are probably more birds in there. So if nothing else, you’ll get to see beating wings. Zigzagging can work effectively, and you can even hunt cornrows that way (nobody said hunting alone was supposed to be easy).

Blockers are a prime resource of group pheasant hunts; but if you are alone, you can look for the blocks the terrain provides. A pond or canal is one. A pheasant will probably hold longer, rather than flush out across a body of water, if pushed to its edge. There is the question of retrieving, though, so carefully consider what you will do if you drop a bird in the soup, in particular if you don’t have a dog who’s partial to paddling. Another consideration is wind. If you point yourself into it, the birds will probably hold longer and fly slower as they buck the breeze.

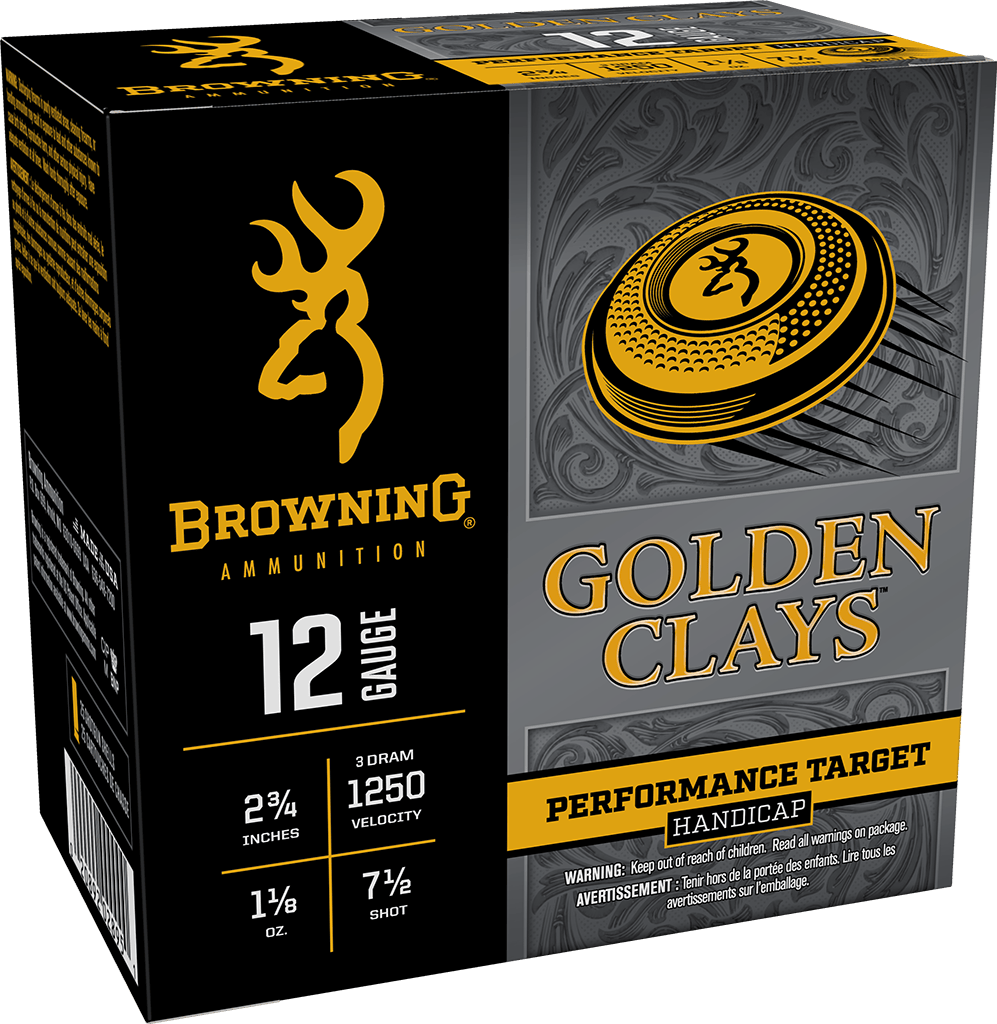

Hunting solo, with or without canine companionship, is unlikely to provide many crossing or overhead or otherwise closer-range shots, so gauge, choke, and cartridge choices come into greater play. From Browning upland loads, the usual suspect is No. 6 shot for ringnecks. When hunting alone, with birds likely to clatter off directly away and at least at a little distance, No. 5s might be an option, especially in 3-inch shells for extra payload. Choking should tend toward the tighter, with Modified not out of line. And for gauge, it’s time to forget finesse and stick to the firepower of a 12. Hold off on low-percentage shots, which may mean a lost crippled bird; but after pulling the trigger, watch the bird until it goes down or you’re sure it’s going to keep flying. If it drops, do not take your eye off where it falls, and head for it right away.

The single pheasant hunter wants time on his side. Just before, and just after, a storm or snow will keep the birds tight to cover; and with a new dusting of flakes, fresh tracks will be visible. The last hour of daylight is also good for finding birds moving between feeding and roosting cover. Look for ground between the two and hunt while the sun lets you.

Follow Browning Ammunition’s social media channels for more hunting and shooting tips and updates on Browning Ammunition supported events and promotions on Facebook, You Tube, Instagram and Twitter.