Fowl Weather

Hunting is as safe as it gets. Safer than golf, far safer than cheerleading! The chance of injury from hunting is a scant 0.05-percent, one in 2,000. For waterfowl hunters, though, the danger comes not so much from the activity as the environment. Duck and goose hunters are more likely to place themselves in the eyes of storms than other hunters. Rain, fog, sleet, snow, wind can all be par for the course for waterfowlers, and are even welcomed by them. Then, as the name suggests, there is water itself.

In every duck and goose season, hunters drown. Overloaded or inadequate boats capsize or swamp, going to and from blinds; or hunters simply fall in. Just teaspoons of water in the lungs can result in drowning. Even if hunters can manage to stay out of the pond or slough, there are plenty of other ways of dying while in the pursuit of waterfowl.

Waterfowlers hope for weather changes to push birds their way. Luckily, weather prediction is spectacularly accurate these days, meaning hunters can usually get good advanced warning on storms coming in. That wasn’t the case in 1940, though.

That year, Armistice Day (that’s what it was called then) looked to be a great one for duck hunters along the Upper Mississippi, in the Upper Midwest, and on the Great Plains. Bluebird weather changed into wind and rain, and the ducks were flocking. Hunters stayed out longer than they might have, absorbed in the shooting. When the blizzard hit, it was too late for many of them to get off the water or to shelter. By nighttime the temperature, with windchill, fell a hundred degrees from where it had stood during the day. For days after, from Ontario to Illinois and Michigan to Iowa, they were recovering frozen bodies. Over 50 died and many more suffered the effects of exposure.

We may have far better information now about what is heading toward us out of the skies, but that does not mean the Boy Scout motto of “be prepared” carries any less weight. Consider the average duck hunter with his shotgun, bulky jacket, pockets full of cartridges, heavy boots, going into the water and trying to stay afloat, let alone swim to shore. Which is why you need some kind of personal floatation device on your body. There are inflatable vests that won’t obstruct movement and float coats that come in camo just for waterfowlers. A set of neoprene waders will keep you both above water and warm. If you are hunting in fields, rather than on water, be sure to have enough waterproof, insulating clothing to protect you from hypothermia.

Always tell somebody back home exactly where you are going to be hunting, even if you will be with a group of other hunters. If you have about $300 to spare, you can buy yourself an emergency personal locating beacon to carry in your pocket, especially if you believe you cannot depend on cell service or your phone’s battery life. And of course, you can rent a satellite phone for a relatively few dollars a day, letting you make a call from virtually any spot on the globe.

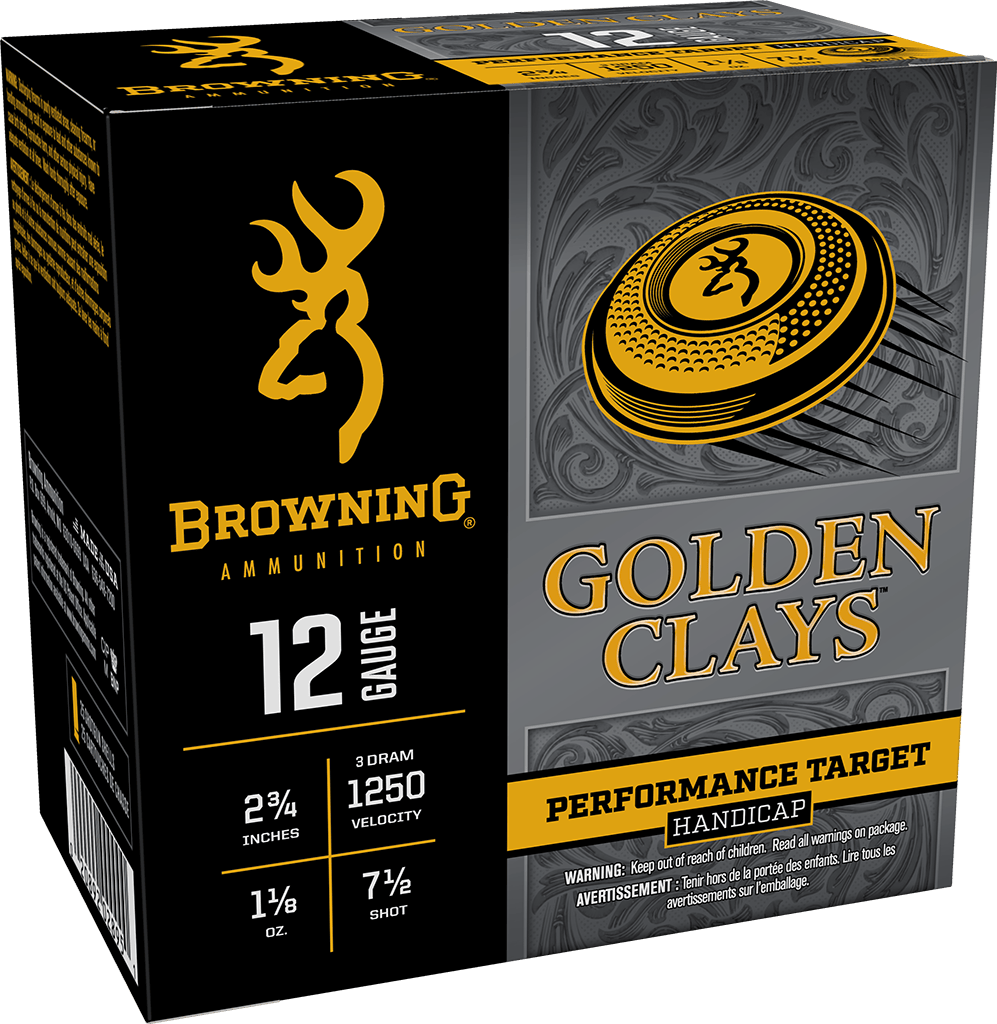

Even something as simple as shotgun cartridges need careful attention when hunting in inclement conditions. If powder gets wet, it becomes less effective, combusting with diminished force. It is also possible for steel shot to rust together into a solid column which can wreak havoc with forcing cones and chokes in shotguns. Frankly, modern ammunition manufacturers have addressed these problems in their waterfowl loads, starting long ago with plastic hulls. Browning, for one, in its BXD shotshells, goes farther by first molding a seal into its wad to prevent water from getting at the powder. They then coat their shot with blue zinc chromate to make it resistant to rusting.

Armistice Day is now Veterans Day, and duck hunters are unlikely to be taken as unawares today by storms as they were in 1940. Yet with waterfowling, it remains very much the nature of the game that hunters can, and do, die. And it also remains the case that they should not, and do not have to, as long as they are fully ready for whatever the conditions throw at them.