Coming Round to It

If we could make shot in the vacuum and weightlessness of space, there would be no trick to fashioning it perfectly round. Natural forces want to press objects, ideally, into round, or spherical, shapes; and unimpeded, such forces work all the better. Thus, the shape of the earth, the moon, the sun. Here on earth, it’s not so easy.

If we could make shot in the vacuum and weightlessness of space, there would be no trick to fashioning it perfectly round. Natural forces want to press objects, ideally, into round, or spherical, shapes; and unimpeded, such forces work all the better. Thus, the shape of the earth, the moon, the sun. Here on earth, it’s not so easy.

Some of the earliest shot, used by artillery in the Medieval ages, was stone, followed by heavier, therefore ballistically improved, cast-iron shot. Henry VIII is recognized as among the first in England to own and use shotguns, or as they were styled in the day “Haile Shotte peics,” the shot made from sheets of lead. It was not until the early 1780s that the Bristol, England, plumber, William Watts patented the process for making shot with a shot tower. He poured measured amounts of molten lead through the air in a multi-story tower and down into a shaft he dug into caves beneath his home. The surface tension of the liquid metal as it fell turned the drops round, the drops solidifying if the distance they fell was long enough. Water at the bottom caught the shot and reduced the deformation from impact.

For almost 200 years, the process remained the same (Watts’s shot tower was operating until 1968!), though now more modern techniques are used. What has not changed is the ballistic performance of round shot, that still challenges every other shot-pellet shape that can be thought up.

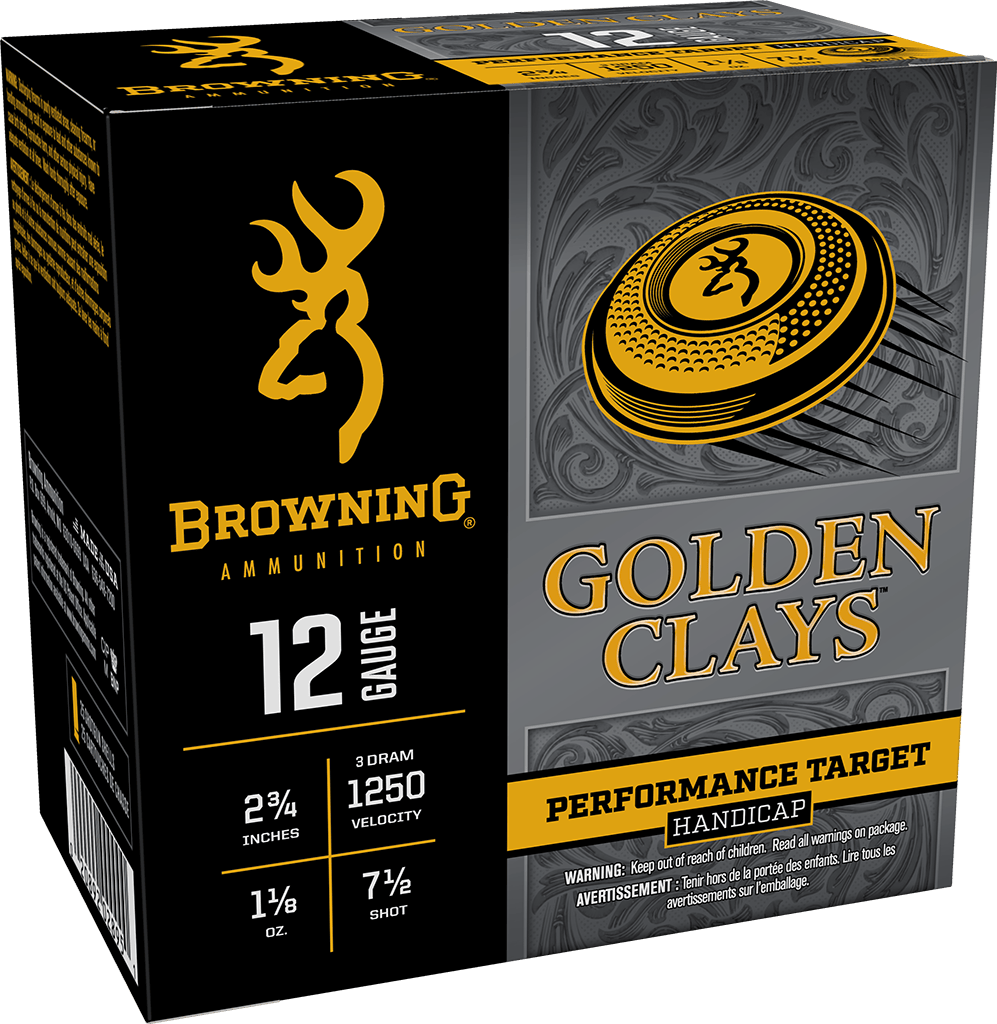

Short of opening a factory in outer space, Browning does as much as it can to keep its round shot round. In their tests against other No. 2 waterfowl shot–some non-spherical and some dual-size loads–their BXD rounds consistently performs better with full, modified, and improved chokes at ranges from 50 to 60 yards, in both patterning and shot count, meaning more pellets on a duck. On a 30-inch patterning board at 50 yards, the 3-inch No. 2 load delivers 67-percent of its shot, 100 pellets. It always matters if you can center a duck in the pattern, but that many shot pellets boosts the odds on those ducks that may fly on the margins.

Pattern is one thing, penetration another. The BXD No. 2 produces 3-inches of penetration in ballistics gel at 50 yards, and 2½ at 60. For big ducks, many hunters consider 1½ inches to be a minimum for lethal hits. I have to wonder: If spherical shot performs best in air, and I think we can all agree that it does, wouldn’t it perform better in its terminal ballistics, i.e., on the duck?

The last step Browning takes with its waterfowl shot is to plate it to prevent rusting in wet condition. The factory hull might be enough to keep the shot dry in wet conditions, but there is still the possibility of condensation, followed by oxidation. By plating its waterfowl shot, Browning helps avoid that.

In addition, Browning goes so far as to nickel-plate its shot for its upland ammunition. Here it is to toughen the outside of the lead pellets, to ensure they remain round out of the barrel and maintain their ballistic advantage down range.

Is round all? Would your rather throw a brick or a baseball? I thought so.

Follow Browning Ammunition’s social media channels for more hunting and shooting tips and updates on Browning Ammunition supported events and promotions on Facebook, You Tube, Instagram and Twitter.