Long Ago and Far Away

The ethics of hunting big game at long ranges are going to be debated as long as hunters take to the field with high-powered rifles. To many, the essence of hunting is stalking within rock-tossing distance. (The old saying among African professional hunters, when it comes to dangerous animals is get as absolutely close as you can, then get 100 yards closer.) For others, “sussing” out a shot at a quarter mile or more–far enough that you can experience the lag time from trigger break to impact and even see the “bullet trace,” the observable wake the bullet creates in the air as it travels at supersonic speeds–speaks to the skill and practice regimen of the shooter, not to mention the level of precision technology in the rifle, optics, and components. And admittedly, when we think of the famous, or maybe infamous, hunters of the past, it is their feats of long-range shooting (true or not), rather than the up-close-and-personal, that come to mind.

Big game can, indeed, be taken ethically at what might once have seemed extreme distances. Shots of 400, 500, even 600 yards and beyond can be made quite accurately, but not literally or figuratively off hand. Making shots such as that require planning, strategy, and at least some amount of teamwork.

First and foremost, before deciding on a long-range shot, make certain you have done everything you can as a hunter to get a close as you can to the animal. If it takes extra work to hike around a ridge or a summit, or even crawling on hands and knees, to cut the distance, to make for a more sure shot, then you owe it to the game and the spirit of fair chase to do so. There will be times, though, especially in hunting not only mountain game but also plains animals such as pronghorn, when that’s it, you can stalk no closer.

If that is the case, do not rush. If you are looking at long-range, the animal is most likely unaware of your presence and is probably going to stay put long enough for you to plan out your shot. (If it’s moving around or traveling through, then you need to rethink the whole idea of shooting at distance.) Get your rifle rest rock solid, whether on a bipod, across a backpack, or using a natural surface to support the fore-end (do not rest the rifle on the barrel), with or without your forward hand beneath it. Get yourself rock solid, too. Prone will likely be the best position, the domain of what the military used to think of as the “gravel bellies,” the expert marksmen and snipers who took out their targets at city-block yardages.

Have a quality spotting scope (magnifying power is open to argument, but certainly something with a maximum of at least 45× to 50×, 65× to 80× frequently raising stability issues; therefore, think about a tripod for the scope, as much as the scope itself), and somebody else to spot for you. The person on the scope can, as they say, separate the sheep from the goats, but also notice that a horn is badly broomed or broken, or that a set of antlers is missing some wished-for tines (and with elk, there is without careful inspection often the chance of misidentifying a five-point for a six–though a legal five is a perfectly fine animal, as long as a hunter knows what he’s shooting at before pulling the trigger).

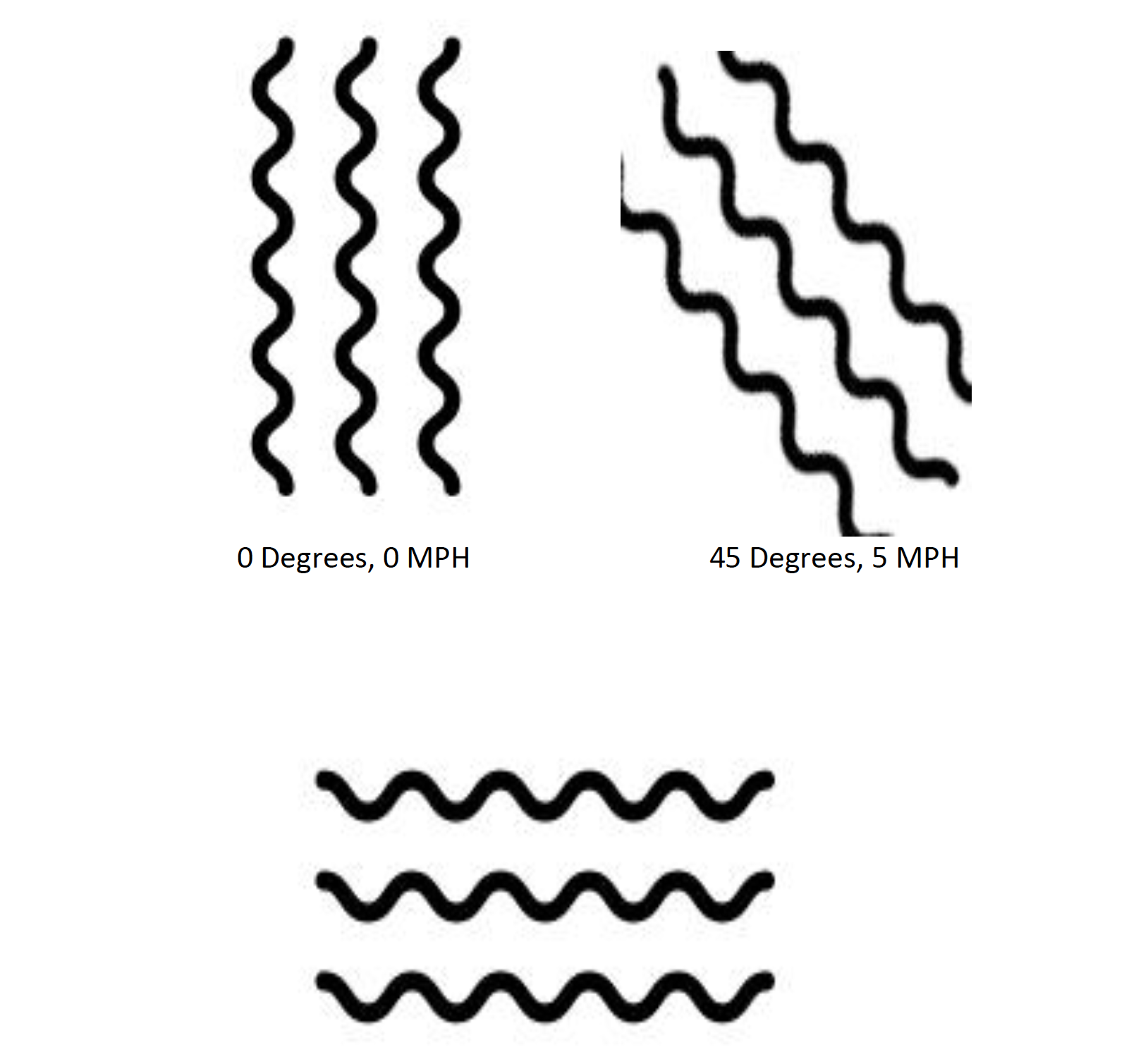

Even with the flight time of a long-range shot, a hunter can lose the animal in the recoil and not judge where he hit if the animal does not roll over dead. His spotter should be able to tell if a shot was in the vitals or not. He can also keep spotting if the hunter needs to make a follow up shot. A long-range shooter does not want to have to alter his solid position after firing, in order to see where the shot went, in case he needs to shoot again. Doping the wind is the most variable factor in long-range shooting, and that is something the spotter can do for the shooter. The simple trick is to focus in on the target, then just slightly turn the scope out of focus. This will bring up the heat haze or “mirage” (visible at distance in almost any weather condition short of pouring rain or falling snow), appearing as a wavy image, at the target range. The easy formula is: straight up-and-down vertical, no wind; 45-degree angle, a 5-mile-per-hour wind, either crossing left or right, depending on the direction of the waves; 90 degrees, at least 10 mph (please see illustrations). This method won’t gauge speeds above that; but that is when the shooter and spotter use an anemometer, the bending of the vegetation, and plain old Kentucky windage.

For the rest, all that is needed is a good laser rangefinder; high-enough-power scope; accurate, high-ballistic-coefficient loads (the higher the BC, the less wind deflection), such as Browning BXS ammunition; and a world of practice, practice, practice: knowing the external ballistics of your bullet out of your rifle, getting a full sight picture through your scope and always concentrating of the lethal area and not the whole animal, having trigger break ingrained into your muscle memory, coordination with your spotter, and what is called “natural respiratory pause”–we are told to inhale and “let out half,” but if we match our shot to our breath’s natural pause, we are not forcing anything and are far more relaxed; really skilled marksman even wait for the pause between heartbeats, the diastolic state!

In the end, as the man said, it’s always better to hunt before the shot, not to have to hunt afterward.

Follow Browning Ammunition’s social media channels for more hunting and shooting tips and updates on Browning Ammunition supported events and promotions on Facebook, You Tube, Instagram and Twitter.