Skeeter Beaters

The chicken or the egg may never be answered. But trap came first, then skeet.

A couple of Massachusetts grouse hunters came up with a game they called “shooting around the clock” in 1920. For reasons that should have been obvious from the outset, laying out a round course had certain drawbacks, especially if you put up a permanent grandstand for the fans. Actually, the course was cut into a semi-circle when a poultry farm was built in the line of fire, and the gunners needed to direct themselves away from it out of simple courtesy if for no other reason. A contest was held and the name “skeet” was arrived at. And for nearly the last 100 years the debate has roiled about which is the more difficult discipline: skeet or trap.

Ardent trap shooters say one thing, dedicated “skeeters” another. Certainly standard skeet involves more different angles, two different trap “houses”–“high” and “low”–crossing targets, and doubles, but closer ranges. Regular trap is single bird, longer distance, offers various angles, but on targets traveling away, without crossing; those birds, though, are constantly lengthening the distance from the shooter as they fly. Is one superior practice more than the other for hunting live birds? Some say skeet for waterfowl and trap for upland game; but almost any practice is good practice: the more you shoot, the better you shoot.

To shoot better skeet, a few tips to keep in mind. Start with the choke. For skeet the three effective choices are Cylinder (C), Skeet (SK), and Improved Cylinder (IC), each one progressively more choke –“Cylinder,” as the name implies, gives no restriction on the bore diameter of the gun barrel. If you are shooting Modified or tighter, you are lessening you chances of getting your shot onto the target, unless you are always very, very good at centering the bird in the middle of the pattern. Interchangeable chokes, such as Browning’s Invector Plus help shooters select the ones that will give them the best patterns.

If shooting a single-barreled gun, then SK would seem the logical selection. For over-and-unders (O/U) and the rare side-by-side with interchangeable chokes, the strategy depends on the way the bird is flying. The general rule is to shoot the bird thrown from the house nearer you as going away, and from the other as coming in. (At the middle station, they are both treated the same.) On an away bird, a tighter choke seems more appropriate, while on an incoming use a more open one. For the sake of argument (and who doesn’t love a good argument?): Use a SK or IC for your first barrel and SK or C for your second, whichever is tighter than the first. (If you want to get inside-baseball about it, on an O/U select for the lower barrel on single and first birds, on the theory that the barrel-rise will be less and easier to recover from on doubles; in a perfect world, you will have the right choke screwed in; but this is not that world, so don’t sweat it.)

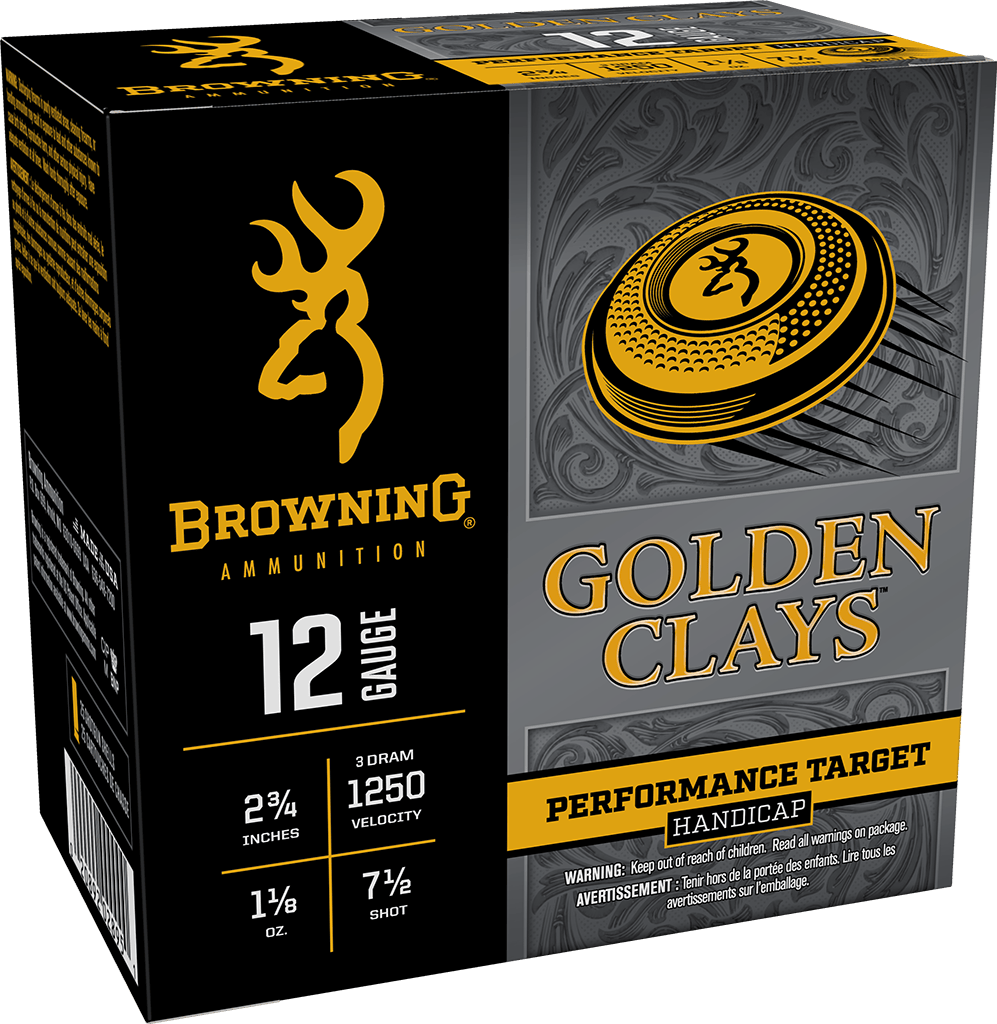

Shot size is another, perhaps endless, source of debate. Frankly, either of Browning’s 7½ or 8 BPT hard-antimony-shot target loads will break birds; but if forced into one or the other, I would pick 8s for skeet for the advantage of more pellets, while wanting the fractionally heavier weight and impact of 7½s for those trap birds trying to make a swift getaway. As far as gauges go, the smaller, the bigger the challenge. (I have heard of competitors explaining that the reason they use 12 gauges in medal contests is because they won’t let them use 10s.)

Skeet is more about anticipation than trap. A trap shooter has less idea than the skeet gunner about which angle the “pigeon” will take when it is thrown. So, the skeet shooter can prepare by positioning himself where he wants to break a bird. At the proper station, pointing your gun in a safe direction, mount the gun, if you shoot with it shouldered (and if you are starting out, shooting “pre-mounted” will prove much easier than shooting from “low-gun”–i.e., the gun butt starting off the shoulder in a variety of positions, below the axilla (“armpit” to the less refined among us), 10-inches below the shoulder seam of your shooting jacket, or between the elbow and the hip, depending on the rules or customs or just the matter of preference–and always be sure to keep the trigger finger pointing in the direction of the muzzle until ready to fire. (Low-gun is more realistic practice for hunting; pre-mounted is for better scores.)

From whichever position, cover with the muzzle at the place in the air at which you want the target to break, preparing your stance to fire there. Now, without shifting your feet, turn back toward the target house. Remember, the bird will be coming fast, so you want to give yourself some room to pick up the target before it jumps ahead of you. Call “pull” and begin to twist from the waist as the bird appears. If starting low-gun, the muzzle should not dip as the shotgun is mounted (this is where empty-gun practice helps with building muscle memory). Cover the bird, swing ahead, fire, and keep swinging. In no time at all you be running 25 straight. Or not.

Truth is, scores are nice, even great. But shooting, then shooting some more, is better.

Follow Browning Ammunition’s social media channels for more hunting and shooting tips and updates on Browning Ammunition supported events and promotions on Facebook, You Tube, Instagram and Twitter.